By Mirah Riben

In every conceivable manner, the family is link to our past, bridge to our future.

Alex Haley

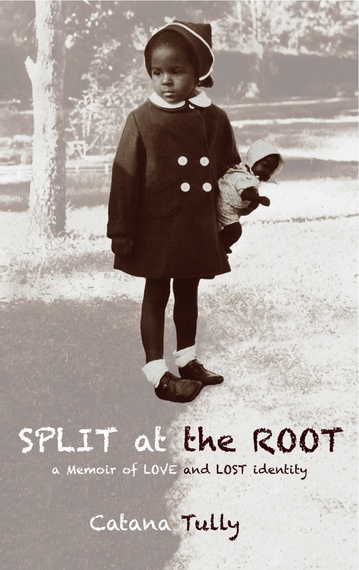

I am not a fan, in general, of adoption memoirs perhaps because I have read too may. Most are elongated, detailed blog posts. Split at the Root: a memoir of love and lost identity stands head and shoulders above the run-of-the-mill adoption memoir. If Oprah was still on their air, this book would easily have made her list of recommended reading for anyone who likes a well-written autobiography. It is the story of a woman with “three distinct races running through [her] veins” yet ‘’no racial or ethnic frame of

Catana was a loved and doted over Black child, raised by privileged White German parents in a German community in Guatemala who gave her everything and anything she wanted.

As a child she loved the story her mother told her of awakening very early one morning and finding Baby Catana floating in on a leaf, not unlike the Pharaoh’s daughter finding Baby Moses. While the truth was far less romantic, Catana’s “adoption” is far from a classic adoption. Born in 1940, her “adoption” was what today would be called open yet her story is replete with many secrets and lies, nagging rumors of her having been “stolen.”

The major theme is racial identity. As a child, Catana was taught that because she was Black she had to excel, leading her to become an actress and model in Europe then marrying, traveling, and becoming a mother. She is also an accomplished artist, an interpreter fluent in three languages, and a professor of cultural diversity. Despite these achievements, she was a Black woman raised in a White world and like many inter-racial adoptees, experienced life in the “neither here nor there.”

“I had not cared that Blacks viewed me with skepticism, but when Whites’ attitude began to be encoded as negative, I had nowhere to turn. It would have been counterproductive to confide in my friends for as far as they were concerned, I had the best of both worlds.”

As happens to inter-racial adoptees at some time in their lives, having to check boxes on forms caused her to question:

“Was I Black? Was I Hispanic? What was my identity? I d e n t i t y… It was as if I was hearing the word for the first time. Slowly, very slowly I grasped, much to my horror (what friends already knew) that I had a problem with self-definition. Never before had I needed to clarify who I was. Others did it for me: I was different. Period. Now I had to say what I was, or what others expected to see precisely in the definition. What box should I mark when I didn’t see me fitting comfortably into any. There was no box marked ‘Exotic.’ Whatever I chose, I felt I’d end up falling into a stereotypical category to be judged, cataloged, and shelved.”

Catana traverses these racial issues and all adoption issues without input or a roadmap from other adoptees or biracial people, which added – for me – a fresh prospective to these issues without clichéd language of the “adoption community.” Had she, however, she would have known it was not uncommon that despite all she had attained, at mid-life Catana’s façade begins to crumble. She finds herself unravelling with “inner turmoil” and “debilitating” feelings of inadequacy despite her accomplishments.

With the help of a skilled therapist, she begins to reexamine her “Mutti” (German for Mommy) who adored her and whom she idolized. Chipping away at the pedestal she had erected for her Mutti, she saw how she had been raised to always be “better than the White ones” in order to be considered equal. It was a mantra. She says: “If I heard it once, I must have heard it a thousand times.” She was raised to feel superior and as a result she saw herself as “whiter” than even her “palest friends.”

“I had excellent, polite manners, was always cleaner – immaculately clean – and my curtsies still flowed with grace long after other girls had stopped doing theirs. I knew I did things better than the lot of blond, blue-eyed kids and I thoroughly internalized my superiority.”

The flip side was her skin color which immediately announced to others that she was Black, a member of a race she had internalized as lesser. While teaching the social aspects of colonialism and the mentality of internalized self-rejection in colonized people, Catana had an epiphany that caused her to wonder:

“Could it be that Mutti loved me, but not the me that I was Negro?

“She colonized me! Came the sudden horrifying, realization. She colonized my brain. She raised me to be what I was not: exclusively European. She taught me her European history, her European values. By so doing, she invalidated my indigenous culture, my people’s history, my own history. She made me reject my heritage and thus reject myself. I internalized my self-rejection just as colonized peoples are taught to internalize their sense of inferiority…”

Catana openly and bravely shares the details of her therapeutic work with unbridled vulnerability, she gifts readers with an inside track on her journey back, untangling the lies and deconstructing fictional aspects of her life in an effort to rebuild a life based in reality. With her therapist’s encouragement, she begins to think about “the woman who carried [her] under her heart, whose placenta had fed [her] for months on end, and who had opened her body for [Catana] to emerge…”

Having found herself unable to continue to live in denial and fantasy, she begins to integrate her authentic genealogical history into who she is. Catana faces her truths, even the painful truths.

“As Adriana, I was born humble, but would have felt secure in Rosa’s [her Black Guatemalan mother] heritage. As Catana, I became Mutti’s polished product, yet insecure and painfully dependent in approval.

“I am both Adriana and Catana, of course, but which one do I crawl into when I need comfort? Which ‘me’ reassures, protects, offers consolation? Which ‘me’ makes me whole? Takes the confusion away? Which one is my essence? Who is my mother when I have both?”

Meeting her father is so rapturous it borders on incestuous as she is swept away by his sensuousness. She sums up their “honeymoon” period and the demise of their relationship as the equivalent of an escalated lifetime.

“At our first meeting I felt like a little girl, loving and trusting him unconditionally…the second time we met…I saw him and related to him as a man rather than a father. That could have been a pre-adolescent stage, when a child is more critical….and [then she] rebelled like a seasoned teenager. No forgiveness [just] adolescent rejection.”

Her father gives her the gift of looking into the eyes of someone who mirrors her back and also a realization that instead of feeling at fault that she brought shame on the family who raised and loved her:

“Had I been in touch with my people’s environment, I would have known about overt and cryptic racism and rejection. I’d have faced prejudice openly just like all my ancestors who had to deal with white people faced racism, rejection, and oppression. It would have been expected…pedestrian.”

She then explores her Black mother, Rosa, and half-siblings who celebrated her birthday every year with a cake and piñata. “and were reminded, indoctrinated, that if ever [she] needed any of them, together or alone, they were to be there for [her] always and at any time.” And she embraces Livingston, the place of her birth. A place of “little to want…and less to have.”

“I am the product of one of those sultry tropical nights, of youth and sensuality, of liquor, rhythm, and sex. Of midnight passion and whispered promises that turn to lies at dawn. I was born at dawn in the heat and palpitation of this sensuous culture. But I grew up so removed, so distant …”

The layers of the onion continue to get peeled, slowly, uncovering a major surprise

One of Catana’s college students, upon hearing her story, compared it to Alex Haley’s Roots. It is indeed at once a contribution to Black literature and adoption books such as Trenka’s The Language of Blood. Whether you have an interest in adoption – or race issues – or not, Split at the Root is a good read.