By Mirah Riben

Adoptive families have been commemorating the day they acquired their adopted children with an annual celebration since at least 2005 when it was suggested in Margaret Schwartz’s book The Pumpkin Patch. The celebration and its name have been the subject of controversy since its inception.

Very recently, adoptive father and poet Patrick Hicks wrote

“Gotcha Day is a beginning — this is undeniably true — but it is also an ending. A door home has been slammed shut forever, and the child has been removed from their ancestral home, their blood ties and their language. These are no small things, and as we go about remembering Gotcha Day in our house, I’m aware that somewhere in Korea is a young woman who must wonder what part of the earth her son landed upon. For this reason, Gotcha Day is charged with emotion. There is joy and sorrow, belonging and longing, home and away. It is a day that sets a young life into motion with a new family, and it is a day that signals an end. Even the term ‘Gotcha Day’ is problematic. It sounds too much like a simple game of tag, and there are undertones of salvation to it.”

Hicks seems sensitive and understanding, but he misses the mark. Despite his awareness of the painful aspects of adoption separation, he continues to “celebrate” it.

The G-Word

Those who continue to hold these celebratory days do so despite valid objections to it. There are two disturbing issues these celebrations create. The most basic aspect of it — its name — is also the disturbing aspect if it. Many find it far more than a playful or simple “game of tag.” The contraction for “I got you” is used by fisherman when they hook their catch and hunters when they take down their prey. It is used to express satisfaction at having captured or defeated someone or something; or having uncovered their faults; exposing them to ridicule especially by elaborate deception.

Merriam-Webster online defines “gotcha” as “an unexpected problem” or “unpleasant surprise.” The fuller definition describes it as an “unexpected usually disconcerting challenge, revelation, or catch; an attempt to embarrass, expose, or disgrace someone.”

Karen Moline, author and the adoptive mother of a child born in Vietnam wrote “Get Rid of ‘Gotcha’” for Adoptive Families magazine in which she says:

“‘Gotcha’ is my typical response when I’ve squashed a bug, caught a ball just before it would have rolled under the sofa, or managed to reach a roll of toilet paper on the top shelf at the store. It’s a silly, slangy word…

“I find the use of ‘gotcha’ to describe the act of adoption both astonishing and offensive. Aside from being parent-centered (‘C’mere, little orphan, I gotcha now!’) it smacks of acquiring a possession, not welcoming a new person into your life… ‘“

Indeed. No one says “gotcha” on the day they get engaged or married. Moline’s blog post elicited pros and cons. She was called too serious and overly sensitive. It also inspired others to blog on the subject. If you have to err, however, is it not better to err on the side of being overly sensitive than possibly hurtful?

Korean-born and reunited American adoptee Mila says G-Day “take[s] a tragedy and coats it with euphemism… it’s almost like you’re celebrating the fact that your daughter has lost everything. It’s as though you’re celebrating the death of a crucial and vital part of who she could have been.”

She writes:

“I have to admit that the name alone makes me wince. I personally think it would be more accurately referred to as ‘You-lost-everything-you-know-but-let’s-not-think-about-that-now-because-WE-are-your-family-now Day’….

“I understand why parents practice it, and I think the heart behind may be right. But the implementation of the good intentions is misguided with the concept of ‘Gotcha Day.’

“I personally think it can, although unintentionally, teach the adoptee that he or she should feel only grateful, happy and excited about his or her adoption. I think it can inadvertently communicate to adopted children that they are not allowed to feel angry, hurt, sad, upset about their adoption.”

Perhaps the most painful G-Day story is that of a family whose son came to them after his “first forever parents” — as they ironically call them — disrupted his adoption after just ten days. How many G-days can one child celebrate?

There is also the fact that G-Day, like re-homing, has its origins in the pet rescue lexicon because it implies caught or trapped. Is this really what we want to model?

An Alternate Name?

Shelly, who has adopted two daughters, says she does not celebrate it because the G-word makes her “squirm.” She prefers “Family Day” instead.

Sophie Johnson was adopted from China, as was Hick’s son. Her family has also changed the anniversary of her adoption to Family Day.

“…sometimes while adopted kids are processing it, their feelings of loss override their feelings of happiness. Gotcha Day is one of those times when we think about our past and how little some of us actually know about it. We think about our biological parents and wish we knew them and could ask them why they didn’t keep us. We think about what our lives would be like, where would we be, what our futures would look like, had there been no Gotcha Day….

“… It’s been said that adoption loss is the only trauma in the world where everyone expects the victims to be grateful and appreciative…. Gotcha Day feels like a day of fake smiles if we don’t acknowledge that it’s also about loss, not just gain.”

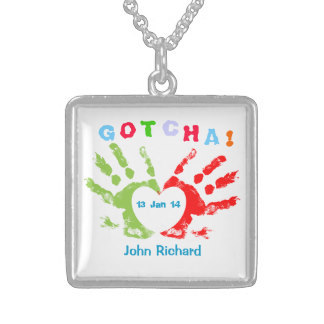

Like a rose, it seems changing its name made it no less “a lot to process.” The fact is that G-Day, or Adoption Day, or Family Day is an artificially contrived day created by adopters to celebrate their happiness and acquisition while also recognizing, perhaps, their child’s loss of roots and heritage. What other loss do we celebrate with a party and gifts such as those for sale here and here and celebration ideas?

Another adoptive parent explains that they don’t celebrate the arrival of their adopted son into their family any differently than any traditional family does: “We celebrate his birthday yearly and his existence daily.” One reason for this “is simply because our oldest son doesn’t get two days to celebrate. We treat both of our children the same, and while adoption is a part of my younger son’s story, it is not his ONLY story.” (Sadly, however, birthdays can also be painful for adoptees.)

The Chinese-born adoptee and contributing blogger at Transracial Eyes and writer for Gazillion Voices adoption magazine expresses his concerns that “for children who may have been victims of trafficking, this phrase can be especially difficult to hear and in some cases triggering,” He says:

“While adoptive parents may be ecstatic the day they meet their children and find it something worth celebrating, the truth is that first ‘Gotcha Day’ is not an exciting or thrilling day in the adoptee’s life. It is terrifying being handed off to strangers who don’t resemble you at all. Though the orphanage officials had told me that my parents were my mom and dad, I was three years old and knew that I had already had a 妈妈 and 爸爸. My reaction to the fear I felt was by remaining silent for over a week. Other children reacted to the stress by refusing to eat or poop or by throwing temper tantrums. One adoptive mother remembers her daughter being placed in her arms. ‘She was shivering and shaking, and my husband and I knew we would never celebrate this moment of visceral pain for our daughter.’

“My last criticism of ‘Gotcha Day’ is that it furthers a rhetoric of child commodification. The bottom line is that children are not something to simply be gotten like a computer or kitchen appliance.”

For those who adopt, adoption culminates years of paperwork which is preceded for many by years of failure to conceive or carry a baby to term. For adoptees it’s a win and a profound loss. For the mothers who bear the children that get grabbed up for adoption, it’s simply a loss. From that perspective gotcha sounds like snatched, which is how many mothers feel about the way their child was taken, coerced, duped, pressured or out-and-out stolen from them. The adoptive parents’ gain is a gut-wrenching tragic loss to the families of birth. To hear of celebrating joy that resulted from their child having been torn from his or her family and heritage is a painful reminder of the entitlement and demand which drives contemporary adoption.

Proponents of this contrived day say their children like it. Why wouldn’t they? Like birthdays and other holidays, most families mark the day with gift-giving. So naturally, kids enjoy it. If it is at all uncomfortable for them, most children are unable to articulate it, as they are many aspects of being adopted.

Adoptee Marley Grenier, who blogs as Bastardette, remembers fondly the gifts she used to get as a child on G-day. As she matured, however, as all children do in time, Grenier had time to ruminate on adoption and being adopted. She began to understand the loss and the politics of adoption. She now says Gotcha Day is an expression of “the avarice, the braggadocio, the narcissism” of adopters, some of whom who also use terms such as “paper pregnancy.” After all, is it not a big party to say “Your loss is our gain”?

In 2013 Grenier expressed the harsh connotations of the word, writing:

“I first heard about Gotcha around 15 years ago. I was immediately squicked. Gotcha sounds like trapping a rat under the stove or grabbing up the last flat screen TV on Black Friday at Wal-Mart. It’s a predatory term. A scary term. A cheap term. A violent term. Gotcha relates adoption to aggressive consumerism; and consumerism to a public act of virtue…”

Adoptive mother Lisa Milbrand, says “‘Gotcha Day’ can be pretty traumatic for kids.” Her family thus celebrates a modified version.

Why do it at all? Continuing to use the term, even recognizing represents both losses and gains, can be hurtful and disrespectful to adoptees and their blood kin. It may be hurting the child whose parents think he is enjoying it, or it may in the future.

Why not openly and compassionately recognize the losses your adopted child suffered before coming into your family… losses which are not limited to, or made better by, one day? Think about it. If your brother or sister died and you took in their child, would you celebrate that day?

Read at the Source: :