By Mirah Riben

“I feel like a stolen heart from a corpse, trapped in a foreign body.” Sunny Jo

“This is not something that gets better over time. Because as you get older, as you live, you learn more and more about what’s been taken away from you. And you learn more and more about the enormity of what’s been stolen.” Cameron Horn

“I feel like a ghost, invisible to the culture and society that brought me here, but also invisible to the community and culture of my birth. My heritage and the cultural umbilical cord having been severed at birth by transracial adoption – an act perceived to be responsible for saving my life.“ Lucy Sheen

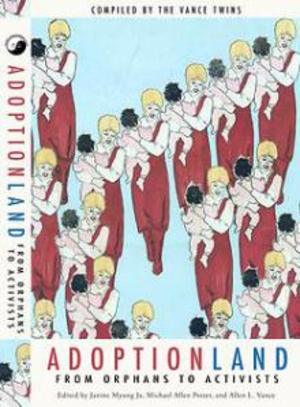

Compiled by Janine and Jenette Vance, AdoptionLand: From Orphans to Activists, is an indispensable contribution to adoption literature. The essays, poems and letters in this compilation reflect the thoughts, the feelings, the souls of those who inhabit AdoptionLand — a place of truth and acceptance for the casualties of the demand for children.

The anthology brings together twenty-eight men and women. Many are internationally and/or inter-racially adopted. Asian babies scattered around the globe like seeds in the wind, hoping some will flourish. One taken from Germany and another sent toGermany illustrating the haphazard irrationality of international adoption and begging the question: how this could be in the best interest of the children?

Like the majority of those adopted, many of the contributors were loved and feel great affection for their adoptive parents. One did not know he was adopted until well into adulthood. Another was adopted at ten years of age by a sexually abusive man after having been abused by a foster family and a “trial” summer adoption. Regardless of their personal circumstances, many grew up to see the fallacies and failings in the adoption process and now work to create change in the system

Interspersed with the voices of these adoptees are mothers and a father who lost their children to adoption. Cameron Horn writes:

“We are the parents of the missing children. …I am a parent of a missing child. I don’t know where she is. I’ve had a reunion. I’ve seen her for five minutes in 32 years. I don’t know where she is.”

Like Horn, for whom the pain of loss increased with time, Lily Arthur says she is still in a state of “trauma and anger 43 years later. I am still trying to come to terms with my imprisonment and the premeditated theft of my only son.”

The Donaldson Adoption Institute recently responded to a comedy film that mocks adoption describing this reality, noting,

“There can be pain in adoption because for many, at the heart of it, is loss. …Adopted people navigate the unique, and at times, complicated experience of knowing there is fundamental loss in gaining an adoptive family.

The world of adoption can be beautiful and it can be painful; most often, this world is a combination of the two.”

AdoptionLand is the place where the two combine. It is the place where those whose lives have been irrevocably changed by adoption dwell. Tinan Leroy describes his experience in the limbo nether land of adoption. On his first trip to back to his homeland, Haiti, he says, “I thought that I belonged to two worlds. It occurs to me now that I do not belong to either.”

Lucy Sheen describes it as “a no-man’s land between two cultures, two languages, and two distinct ‘what might have beens’.” It is in this place, says Sheen, that adoptees wander without “benefit from the reflection of society’s mirror re-enforcing our physiognomy.” Identity is, she says, “elusive.”

Tinan Leroy also describes feeling “caught in a no-man’s land” and says, he

“[W]anders in a no-man’s land, ill-defined, trying to build upon my shaky foundation, while it continually gives way under my feet. Sometimes, I struggle to keep my balance and not get lost in the grey area of adoption. Sometimes I lose my grip completely and falter.”

Another recurring theme in the writings of these adoptees is that of “gratitude.” Tinan Leroy, who was born in Haiti and adopted by an affluent single mother in France asks, “How can you thank someone for removing you from family roots?”

Trace DeMeyer and her brother lived, as many adoptees do, silently and secretly, fearing that they could be “abandoned again, put out on the street, sent back to the orphanage, or back to foster care.” As a result,

“By trial and error, Joey and I learned not to bring up the subject [of their origins] and to act grateful. We could not protest the absurdity or secrecy we lived under. It was never clear how they would respond to questions… we knew showing too much interest in our adoption was definitely risky. If we asked too many questions, they’d think us ungrateful.”

Sunny Jo was kidnapped in South Korea and adopted in Norway where she was often told how lucky she was because of “the assumed benefits” of living “a privileged and affluent life in Norway.” Like DeMeyer, Sunny Jo was “made to feel guilty” for wanting to know about her beginnings.

“There was simply no room for my loneliness and feelings of alienation (as all space was consumed by the happiness of my parents and society’s colour blind conviction of having done ‘something good’ by ‘saving’ me… to show anything but gratitude… would be like slapping the faces of the adoptive parents, who loved me… So I carried my pain alone, wearing a mask for fear I might destroy someone else’s illusion.”

Lucy Sheen says she is “profoundly grateful for having been adopted” but she is not beholden to her adoptive parents and owes them nothing. She credits a good therapist for helping her untangle and singularly identify and simultaneously accept these seemingly contradictory concepts.

Such help is not easy to find. Often, the reality of the inhabitants of AdoptionLand runs contrary to the popular myths of adoption as a win-win which, even if it were true, takes a three dimensional phenomenon and views it from only two perspectives, ignoring the third.

As a nation, we have come to embrace those with the courage of those like Caitlin Jenner who speak out about the pain of living a lie. Veterans of war are encouraged to not suffer in silence with PTSD but to seek help. We do not diminish their invisible wounds by suggesting that speaking openly of it was unpatriotic. Yet because adoption is held in high regard and generally improves the socio-economic status of the adoptee, their traumas are downplayed or totally dismissed. It is time we accept that adoptees and their parents of birth often live with PAST: post adoption separation trauma, regardless of how much love they receive or feel in their adoptive homes.

Peter Dodds describes how he “learned to live with the anger of abandonment like someone who slowly disciplines themselves to accept the perpetual pain of a debilitating physical injury.” Michael Allen Potter, whose name was changed three times before his tenth birthday writes eloquently of not knowing what box to check because he did not know if he was South American, Central American, Hawaiian, or Samoan.

What do the contributors hope to accomplish? That is as varied as are their experiences. Khara’s (South Korean born, adopted in Norway) dream “is for adoption to end” while Vanessa Pearce (born in India, adopted in Canada) wants “to end the myth that adoption always lead to a better life.” Peter Dodds (born in Germany, adopted to the US) would like the removal of children from their homeland to be a last resort and Lucy Sheen (who says she was “made in Hong Kong and exported to the UK”) wants the same for transracial adoption. Arun Dohle (born in India, adopted in Germany) wishes “for justice for all families who have been separated by adoption.”

As the word “activist” in the title indicates, many of the contributors are doing more than dreaming or wishing. Dohle is co-founder of Against Child Trafficking. Another contributor, Janine Myung Ja, is co-creator of “Adoption Truth and Transparency Worldwide Network.” Tolbias Hübinette (born in South Korea, adopted in Sweden) was instrumental in founding “Truth and Reconciliation for the Adoption Community of Korea.” All are actively trying to eradicate the corruption and exploitation that adoption is riddled with.

AdoptionLand is a vital contribution to a new genre of books, films, documentaries, and blogs intending to #FlipTheScript on adoption by giving voice to those who have been muted, disregarded, and marginalized as disgruntled, “bitter” or “angry.”AdoptionLand should be required reading by adoptive and pre-adoptive parents, anyone considering placing a child for adoption, lawmakers, all who work in the field, and all who are concerned with social justice, human rights, and child rights. It is also highly recommended for anyone wanting to know what it’s like to be adopted.

It is imperative for us to as a society, if we are concerned with the lives and care of our most vulnerable children, to hear from adults who were adopted. As we continue to import and export children to meet a demand for adoption, it behooves us to ask why many in the adoption community are less than enthralled with a process that was supposed to help them and improve their lives.

Read at the Source: :